The Strong Will Suffer What They Must

Vaclav's Grocer and American Hubris

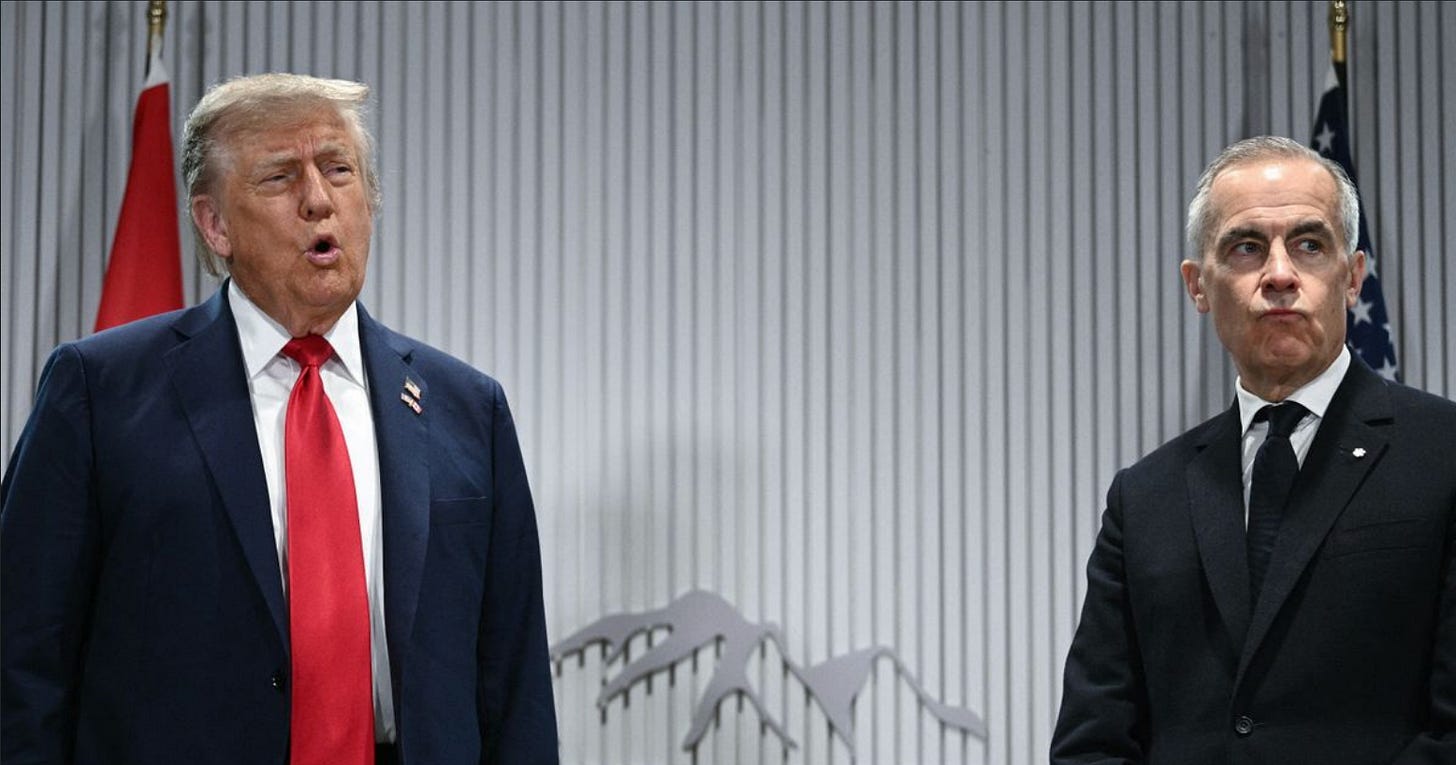

Mark Carney’s surprise manifesto at Davos got a lot of attention for presenting a big vision for the world but also, can I just say: Thucydides and Vaclav Havel in the same speech? The guy sure knows how to tug at my heartstrings. Is this what it feels like being pandered to? Let me just bask in it for a moment.

Usually it’s dangerous to have an intellectual in office, but Carney comes from the world of finance and therefore has the requisite amount of cynicism. So it’s only right he opened his speech by quoting Thucydides: “The strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.” This aphorism, he added, “is presented as inevitable, the natural logic of international relations reasserting itself.” As the rest of his speech suggests, there’s nothing natural about it.

People who consider themselves tough-minded pragmatists love to pluck this line from the Melian Dialogue. They invoke it as timeless wisdom about power politics and a corrective to liberal delusions. “We live in a world, in the real world, Jake, that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power,” Stephen Miller said in a recent CNN interview. “These are the iron laws of the world since the beginning of time.”

This is the governing philosophy of Trump’s second term, and it’s also exactly what brings down hegemons.

The year after Athens delivers that famous ultimatum and brutalizes Melos, it launches the Sicilian Expedition. This act of imperial overreach destroys a massive portion of its fleet and army. Its alliance begins to fracture as the subject states, tired of Athenian arrogance (like the kind echoed by Miller), sense weakness and revolt. Within a decade, Athens has lost the war. Its walls are torn down and its empire is dissolved.

The Melian Dialogue is not endorsing a timeless law of global politics. It’s showing us Athens at the precise peak of its imperial hubris: the moment when a great power becomes so convinced of its own invincibility that it can no longer perceive its limits. Does that sound like anyone else right now?

But their fall only proves the point, someone inevitably responds. They became weak and suffered what they must, right? No. The Sicilian disaster was not just some unrelated streak of bad luck. The same hubris that led Athens to dismiss diplomacy as irrelevant to the strong is what led them to believe they could conquer Sicily.

The failure of self-knowledge, and the inability to see your own limits — or worse, seeing yourself as exempt from these limits — is what destroys great powers. If there’s one timeless lesson of history we can extract from the Peloponnesian War, that would be it. But it’s not the lesson Trump or Miller have internalized.

Despite what self-proclaimed realists like Miller believe, rejecting imperial hubris does not require the embrace of mushy liberal beliefs about morality or global justice. It’s not about the weak eventually prevailing over the strong, or some other feel-good nonsense. For all their faults, actual realists (the ones who write books but don’t make policy) recognize the quote for what it is: pragmatic caution about strategic over-reach.

The Greengrocer’s Revenge

Carney then pivots to something clever: Václav Havel’s greengrocer. Every morning, the greengrocer places a sign in his window: Workers of the world, unite! He doesn’t believe it; no one does. But he places the sign anyway to avoid trouble, to signal compliance, to get along, etc. And because every shopkeeper on the street does the same, the system trudges on. “Not through violence alone,” Carney says, “but through the participation of ordinary people in rituals they privately know to be false.”

Carney’s argument is that for decades, middle powers like Canada have played the greengrocer. They placed the “rules-based international order” sign in the window. They knew the story was partially false, that in many places the liberal order was not liberal or even orderly. That “the strongest exempted themselves when convenient, that trade rules were enforced asymmetrically, that international law applied with varying rigor depending on the identity of the accused.”

But it was a useful fiction so long as American hegemony provided public goods: open sea lanes, stable finance, global trade, collective security, frameworks for resolving disputes. It provided a sense of stability or at least acquiescence to weaker states. Not every time, but enough that they would keep the sign in the window.

“This bargain no longer works,” Carney said. “We are in the midst of a rupture, not a transition.”

What Havel knew, and what American MAGA triumphalists have forgotten, is that power built on performed compliance is fragile in a very specific way. It depends on the continued willingness of the powerless to keep performing. The moment the greengrocer removes his sign, the illusion begins to crack, because his refusal reveals that the whole edifice rests on a mutual agreement. For countries like Canada, their part of the agreement was to ignore the liberal order’s partial hypocrisy in order to reap the benefits of cooperative coexistence. But that lasts only as long as the hegemon makes cooperative coexistence possible.

The self-proclaimed pragmatists who quote “the strong do what they can” imagine this as a stable equilibrium, a description of how power works forever. But the Athenians who deliver that ultimatum to Melos are not wise statesmen seeing clearly. They’re men drunk on their own power, ready to sail into catastrophe.

Carney seems to be betting, I think correctly, that America under Trump has reached its Melian moment: maximum confidence, minimum self-knowledge. Trump’s tariffs-as-leverage obsession assumes permanent asymmetry, that the United States can weaponize economic integration indefinitely while its targets have no choice but to comply.

But the greengrocer can remove his sign. Supply chains can diversify. Alliances can hedge, as they have already. Each act of coercion accelerates the erosion of the compliance that made America’s global order effective to both its originator and its subjects.

What does it mean for middle powers to take down the sign? Carney lays out a proto-doctrine for middle powers. To begin with, refuse to live in the lie. Stop invoking the rules-based order as though it still functions. Call the emerging system what it is: a world where the most powerful increasingly pursue their interests using force and economic statecraft as weapons of coercion. But most importantly, reduce the hegemonic leverage enabling this coercion. Countries earn the right to principled stands, he said, by reducing their vulnerability to retaliation. Rather than waiting for the hegemon to restore an order it’s busy dismantling, create your own institutions and agreements that function as intended.

“Hegemons cannot continually monetize their relationships,” Carney continued. “Allies will diversify to hedge against uncertainty. Buy insurance. Increase options.” He got a standing ovation at the end of his speech, which I’m told is an unusual reaction at Davos. I think it resonated not just because he’s offering a bigger vision, but because it names what everyone in the room already knows but still hesitates to say out loud: the old bargain is dead and the grocer’s sign must be taken down.

This is the insight that Melian Dialogue quote-mongers typically miss. Power that rests on the performed compliance of others is more fragile than it looks. The strong do what they can, until the moment they discover that “what they can” was always bounded by what others were willing to tolerate. Athens found out in Sicily; the question is where America finds out.

(P.S. Last week I had a piece in Foreign Policy on the history of US presidents calling on oppressed people to rise up, only to abandon them when the crackdown comes. I argue this failure is not an unfortunate side effect but is built into the process itself. You can read the whole thing free here.)