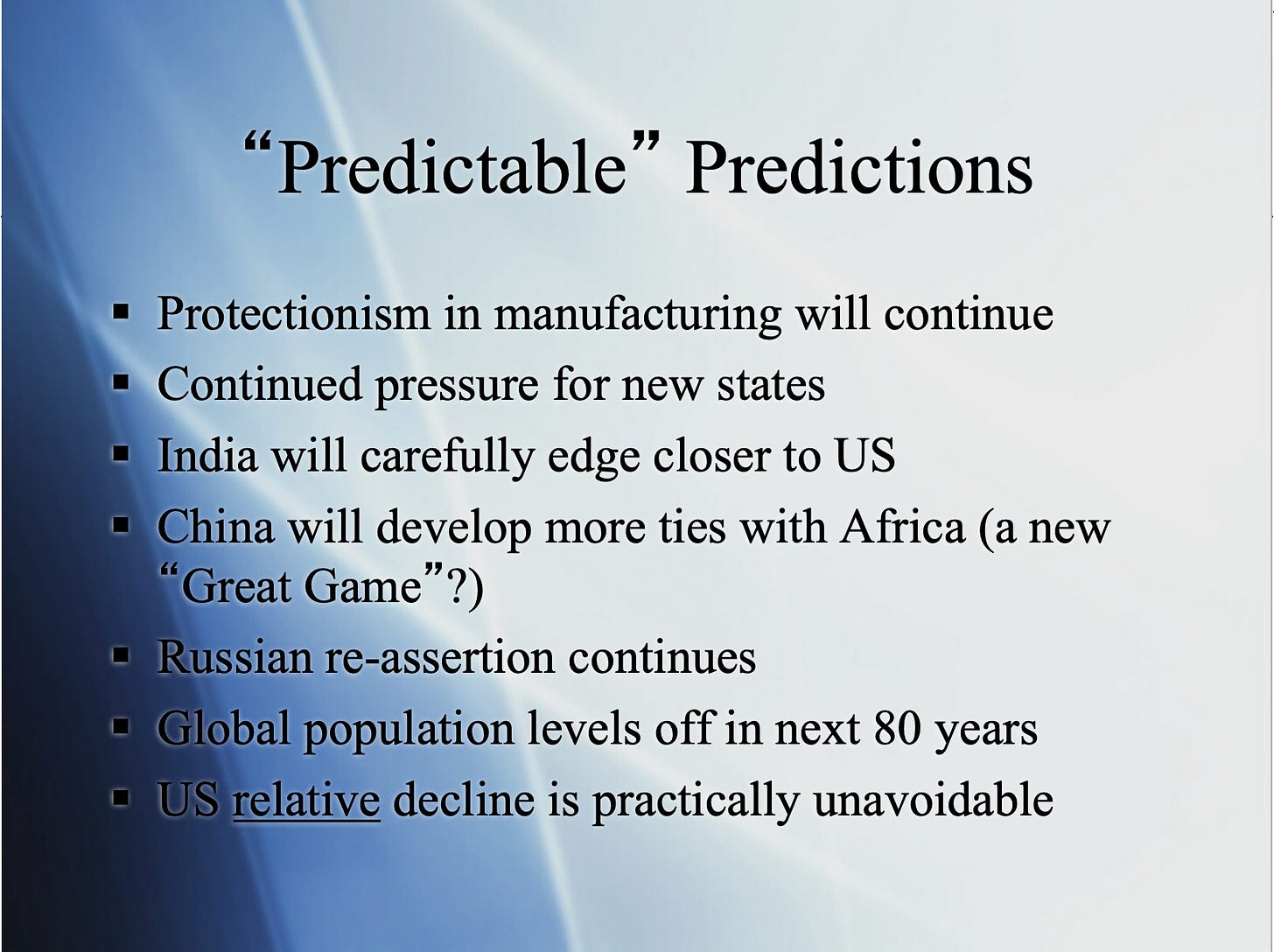

The first time I taught Intro to IR, as a graduate student in the early oughts, I saved the last slide for a list of predictions about the future of global politics. Setting aside the overall quality of this (pretty anodyne) forecast, my second bullet point—the idea that we will see more states — has basically proven false. Only three new countries have been created in the last 30 years: East Timor in 2002, Montenegro in 2006, and South Sudan in 2011.

But you have to understand where I was coming from. There was a huge burst of state creation after the Soviet collapse, and many independence movements seemed to be gaining ground in the following decade. But, as it turns out though, the principle of territorial integrity is even stronger than the principle of national self-determination. Since World War II, powerful states have been reluctant to allow changes in borders, partly because of a lingering aversion to territorial conquest.

State birth and death since 1900. Interesting to see how much global shocks have influenced state creation.

As with many things, this norm now looks to be upended. The idea of border changes and territorial conquests has become much more normalized since Russia’s 2022 invasion. Three years later, Trump is not only saying Russia should get to keep parts of Ukraine, but that the US should get involved in the game too — taking over Greenland, or Canada, or the Panama Canal, who the hell knows at this point. Whether he’s serious or not, the point is clear — the United States, the most powerful country in the world, no longer sees territorial integrity as an important element of the global order.

So what does that mean for the several dozen independence and separatist movements currently operating around the world? In a recent piece for Foreign Affairs Ryan Griffiths (a friend of mine and a professor at Syracuse) and myself made the argument that Trump might seem to present an opportunity for some groups, but for most of them the outcome will be bleak:

For some secessionist groups, this is certainly good news. Independence movements no longer must prove that their cause is just or essential. Instead, they may simply need to align with powerful countries, especially in strategically important areas. Trump’s preference for personal diplomacy could also help separatists, provided that they have charismatic leaders who can sidestep cumbersome institutional diplomacy and court the American president himself.

Yet Trump’s rejection of international norms is a double-edged sword…Independence movements typically justify their existence using the language of human rights and self-determination, which Trump disregards. Rather, this U.S. president favors strong, brutal rulers over fledgling upstarts. He has aligned himself with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Russian President Vladimir Putin, who have used killings and other kinds of violence to suppress Kurdish and Chechen secessionists, respectively. Trump does not care about impoverished separatists if they cannot provide him with immediate rewards.

[F]or those that Trump sees as strategically useless, he will either change nothing or make life more difficult. In a system in which recognition depends on leverage rather than law, more movements could try their luck at gaining independence. But without consistent norms or protections, success will remain rare and failure will become more dangerous. More breakaway regions may receive some form of recognition, but it would be weak and partial—contingent on whether their leaders can keep aiding more powerful states. And the world as a whole will experience more bloodshed, as both governments and separatists, unencumbered by global sanctions or normative restrictions, become more assertive.

Read the whole thing if you’re interested, it’s available for free. The question I wanted to raise here is: do we need to think more seriously about how the international system influences state formation? We are used to talking about state formation in terms of ruling groups consolidating a monopoly on legitimate violence over a territory. In historical institutionalism, we talk about roving bandits becoming stationary. In comparative politics, we talk about systems of patronage, or local warlords competing over resources. Obviously the distinction between external and internal is hard to maintain here, as Tilly’s work shows, but a lot of the analysis takes place at the local level - the intense power rivalries that accompany the consolidation of rule. As a result, conventional explanations of state formation often emphasize the internal factors that undermine or strengthen institutional development — like divided ethnicities, class relations, nationalism, or various competing social forces within proto-states.

Look again at the graph above. It’s undeniable that state formation over the past 100 years or so rarely happens in isolation from broader global influences. Major shocks to the structure of the international system have consistently led to bursts of new states, as shown in the spikes. These hegemonic upheavals shape boundaries after major wars and create windows of opportunity for secession and decolonization.

Ryan, my-coauthor, has elsewhere argued that the success of secession movements actually depends not on local factors but on the intensity of competition in the international system. When the system is competitive, as during the 19th century, secession movements face huge obstacles against powerful states who want to expand and consolidate their territory. By contrast, a relatively peaceful international system (as after 1945) facilitates the success of secession movements and thus the creation of new entities. If that’s the case, a more competitive international environment suggests the number of states will actually shrink, not grow, in the next few decades.

I think it’s hard to deny that modern state formation is linked to abrupt changes in the international system. The question is what this means for our theories of state formation and institutional evolution. We already see that broad systemic forces have repeatedly intruded upon the local processes of institution-building. If that’s the case, how does the international system shape the organizational variety of state formation?

The story isn’t just about who wins local power struggles. It’s about which local struggles get the great power recognition. In our piece we called this “the new price of statehood”: strategic alignment, transactional utility, personal charisma. And as recognition becomes more contingent, so does sovereignty itself: less a settled status than a temporary bargain struck in the shadow of great power whims.

In general, I think scholars of state formation, especially on the international law side, underestimate how much the incentives for state creation reflect the preferences of great powers. For example, decolonization accelerated after World War II largely because it reflected the preferences of both the US and the USSR. But that moment of alignment between normative ideals and great power interests was rare. Today, we’re headed in the opposite direction: the great powers are aligned in the belief that they belong to an exclusive club, in which only a few countries possess true sovereignty while everyone else must follow orders within their spheres of influence. That’s more than a shift in incentives for secession, but a change in the meaning of sovereignty itself. For most groups looking for independence, it will not be a good one.