We are all deep in hell, each moment of which is a miracle.

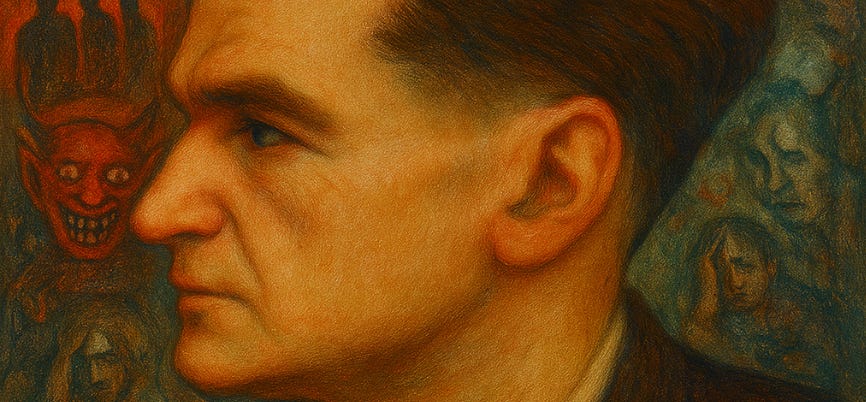

Review: The Trouble With Being Born (1964)

There are only two types of philosophers: funny (Socrates, Montaigne, Voltaire, Nietzsche) and not funny (Hegel, Kant, Sartre, Rawls). Whatever his flaws, Cioran belongs in the first group. He is often described as morbid but once you read a little you realize he is above everything else a troll. You cannot take seriously a man who says you should not kill yourself because by the time you’re ready, it’s too late.

The book is a collection of fragments, none longer than half a page. Books of aphorisms are uneven by nature and this is true here. But the ones that stand out have an amused, resonant bleakness: “All great events have been set in motion by mediocre madmen,” he says, as if reading the news. “Which will be true, we may be sure, of the end of the world itself.”

I suspect the book’s appeal comes from its strong vibe of relaxed disillusion: “We have convictions only if we have studied nothing thoroughly,” he concludes. True belief is more dangerous than malice because it corrupts normal people who otherwise respect social customs. As a result “the worst crimes are committed out of enthusiasm, a morbid state responsible for almost all public and private disasters.”

In a long and otherwise admiring essay, Susan Sontag called Cioran “another recruit to the melancholy parade of European intellectuals in revolt against the intellect”. Ultimately he is too cynical to be affecting. He rejects too much of humanity with his little smirk. But there is something reassuring about his commitment to irony as a way of overcoming the tragedy of life. What more do you expect from a mid-century Eastern European? The title of this post, another one of his aperćus, sums up that worldview pretty well.

That’s why, for all the apparent self-hatred, the book gives zero indication of mental anguish. In fact depression itself is a kind of vanity: “He who hates himself is not humble.” The rejection of grand ideologies gives Cioran a surprised, almost giddy detachment, filled with self-contempt but made bearable by self-awareness. “I have all the defects of other people,” he says, “and yet everything they do seems to me inconceivable.”

Occasionally there is a sharp sociological insight: “If you want to understand a nation, read its second-rate writers; they alone reflect its true nature.” Reading that I thought of course, an obvious corollary to the idea of great authors transcending their time — but it takes a real misanthrope to point that out. As a student of decay, Cioran is also invested in history as a series of errors: “Each generation lives in absolutes: it behaves as if it had reached the apex if not the end of history.” Note the phrase 17 years before Fukuyama.

As a quick (almost single-sitting) read, the book was fine for what it is, a kind of sustained dark joke. But there is too much filler between the punchlines to move it above a clever provocation. I get why some people love the book. It offers a kind of inoculation against despair. But it does so only by building up a shield against the world. Maybe that’s fine, sometimes a detached shrug is all you need. But sometimes it makes for a kind of intellectual timidity. And as Cioran says, “Nothing is worse than the coarseness and meanness we perpetrate out of timidity.”

What an incredible push notification to receive during a contentious work meeting

I feel that the second-rate writers are a fair guide to the received wisdom of a nation, the nation as it understands itself. But to truly understand a nation, the third-rate writers are a more reliable guide.