Geopolitics, But Make It Dumb and Personal

Why we should think seriously about Trump’s neo-feudal order—even if he doesn't.

It’s dangerous to talk about any kind of global “order” under Trump, and more so for academics, who love to impose sophisticated frameworks onto brain-mushed policies. But insane people still create orders. Hitler attempted a fundamental transformation of the international system while out of his mind on meth and barbiturates. His regime was contradictory, unstable, and driven by personalist manias, yet it also tried (and for a short time, succeeded) in forming a new political order whose destruction reshaped the world.

The idea that a global order has to arise from rational or self-conscious planning is itself a kind of academic vanity. Power shapes political arrangements whether it’s wielded carefully or not. In Trump’s case, chaos creates its own set of expectations. For all the volatility and stupidity of individual policies, Trump’s fundamental views on the international system, expressed both in his statements and his policies, have been remarkably stable over the years.

These core views include: the dominance of great powers, the conditionality of alliances, the weaponization of trade, the irrelevance of institutions, and the personalization of diplomacy. Most of these are self-explanatory, I hope, though here’s more detail from a recent piece I wrote for the New Republic. I don’t think they are particularly controversial as consistent elements of his worldview, even if Trump hasn’t always adopted them self-consciously.

Where do we place this “order” in the context of IR theory? It’s obviously directed against liberal globalists but it’s not realist either. The classical realism of Morgenthau and Kissinger focuses on the careful management of state power, the preservation of stability, and the rational pursuit of national interest. Trump’s approach is instead erratic and personalized. He disregards long-term strategy in favor of spectacle, making decisions based on loyalty, grievance, whim, domestic optics, who knows what. He bullies adversaries and allies without balance or sequencing, violating basic realist principles of coalition-building and threat calibration. All this reflects not realism but impulse.

Most fundamentally, Trump replaces the realist idea of “national interest” with patronage and personal rule. Classical realists view diplomacy as a means of advancing state power, Trump treats it as a stage for transactional deal-making between strongmen. This worldview is hierarchical, mercantilist, and almost pre-modern – pre-modern in its explicit rejection of Westphalian sovereignty even as a pretense, in its demand for vassal-like tribute and gratitude (how many times must Vance demand thanks?), in its elevation of kleptocracy and brute force above all else. What emerges is not realism but a kind of vulgar pre-politics that prizes loyalty over legitimacy and short-term gain over systemic stability.

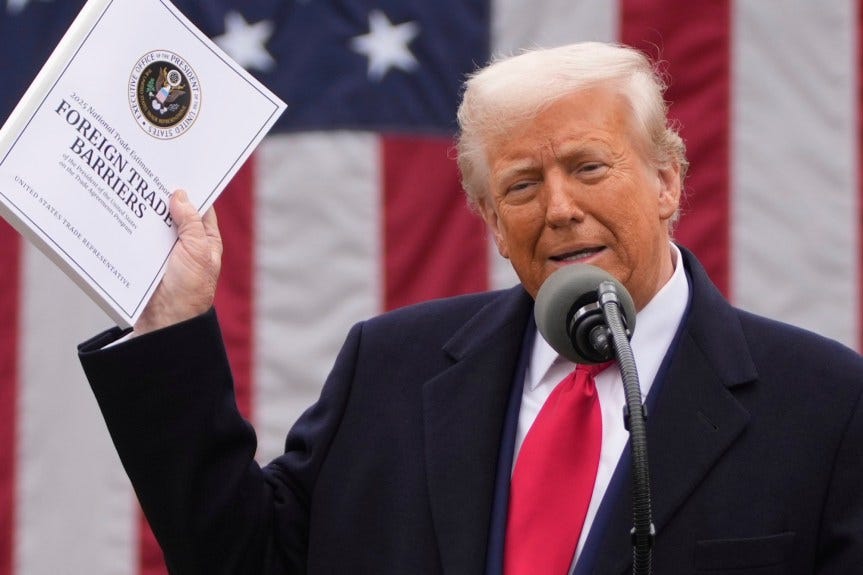

It’s not even a capitalist order. It’s a vision of economic life that sees trade not as a source of mutual growth but as a weapon of dominance. This is where Trump has really separated himself from the conservatives. The neoliberal belief in global markets as arenas of cooperation governed by rules is gone. In its place is a system where economic exchange serves political power, tariffs punish the weak, and supply chains are repatriated by force. It rejects capitalism in the sense that it no longer treats markets as autonomous or sees trade as a mutual good.

What comes out is a kind of neo-feudal regime where the global economy is no longer governed by rules or prices but by power and favor. This is what I mean by pre-modern. Allies are told to pay for protection. Corporations are pressured to show loyalty. Agreements are replaced with ad hoc deals, brokered not through institutions but by personal decree.

This is not the liberal order created after 1945, or even the balance-of-power realism of the 19th century. It’s closer to palace courts and tributary arrangements, orders maintained through personal bonds of obligation rather than formal institutions.1

Here is why I think it’s worthwhile trying to figure out the contours of a Trumpian order. In the spring of 1941 American conservative James Burnham published a book outlining his own vision for a global order. Looking at Hitler’s success, Burnham predicted a post-democratic world centered around a few powerful blocs he called “super-states”. These great powers would exercise complete dominion over their own designated regions while locked in perpetual rivalry with each other.

Burnham thought the United States, as one of the rightful super-states, should “draw a ring” around the Western hemisphere, securing the Panama Canal and reducing Canada to “a satellite”. This new world would be governed not by international law but by personal dealings among the great powers, who would control the sovereignty of weaker states and suspend it as they wished.2

Trump has not read Burnham, of course. (Though Bannon definitely has, and most likely so has Yarvin.) But his book does lay out a reactionary global order that in some key ways resembles Trump’s. Why? They differ in some ways too — Trump sees a lot more room for great power accommodation instead of rivalry. But the point being, it’s not enough to say that Trump is singularly idiotic or incoherent in his approach, and we should therefore give up trying to think about his “order” lest we sanewash his policies. In international relations theory, we still don't really have good understandings of non-liberal orders, or reactionary orders, in part because they are not articulated via clear principles by its supporters. It would be strange to pretend reactionary global orders cannot be theorized or have no elements in common just because their promoters are incoherent sociopaths.

In the waning years of the USSR, Gorbachev would regularly retreat to his dacha to produce theoretical treatises on communism, perestroika, and the global order. It’s never a good idea for a Russian leader to get too deep into theory or history. We saw what happened with Putin. In any case, no such treatises is forthcoming from Mar a Lago. It’s not that Trump understands multipolar tributary systems or whatever — it’s that his actions are often best understood as consistent with that model. Once we make sense of his views for the post-liberal order, his bizarre treatment of Canada, Russia, Greenland, and others becomes a lot more legible.

In social science we routinely describe the behavior of states and leaders in terms they themselves don’t or can't use. I think that’s okay as long as we don’t get too self-important about it. The mistake is expecting a blueprint or a plan. Sometimes order emerges not from design, but from repetition and the gravitational pull of hegemonic power absent restraint. Of that we have enough.

Not every element of this worldview is novel. Realists have spent decades questioning the utility of multilateral institutions. NATO burden-sharing has been a point of contention for decades. Great power spheres of influence are as old as geopolitics itself. What sets Trump apart is not the originality of any single position but the way he fuses them into a confrontational vision that challenges the foundational norms of the postwar American order, at a time when that order appears weakest.

A lapsed Trotskyite, Burnham had come to believe that history was ushering in a new form of rule by a technocratic elite. The Depression demonstrated that capitalism “was not going to continue” much longer, he thought. He pointed to growing parallels between Stalinism, Nazism, and the New Deal and predicted that liberal capitalism was soon be replaced by a technocratic and illiberal “managerial society.” As a result, despite superficial ideological differences, the super-states would share the same common logic of post-liberal governance marked by surveillance, propaganda, and central planning. Burnham went on to become a founding editor of The National Review and was later awarded the Medal of Freedom for his anti-communist theories by Ronald Reagan.

One thing to keep in mind is that this can all be true, but at the same time Trump can simply fail to achieve the entity his policies are pointing towards. Other countries don't seem very willing to co-operate with him.

Well I must say I was surprised to receive notification for this post, it's indeed been a while.