A few days ago Microsoft published a list of the 40 jobs most likely to be replaced by AI. The first two entries are translators and historians, which made me laugh. The two jobs have one thing in common — they are acts of interpretation that are never recognized as such by outsiders. It’s probably self-evident in the tech world that history is a matter of assembling facts. A kind of mechanical curation, like sweeping loose pebbles into neat piles. This delusion is part of a larger hubris— the belief that facts can be wrenched from their social context and made shinier, more objective in the process.

But as Goethe said, every fact is already a theory. That’s why facts cannot save you. “Data” will not save you. There can be no objective story since the very act of assembling facts requires implicit beliefs about what should be emphasized and what should be left out. History is therefore a constant act of reinterpretation and triangulation, which is something that LLMs, as linguistic averaging machines, simply cannot do. E.H. Carr wrote about this sixty years ago: “The belief in a hard core of historical facts existing objectively and independently of the interpretation of the historian is a preposterous fallacy, but one which it is very hard to eradicate.” The facts never speak for themselves; the historian always speaks for them.

The translator’s case is less obvious. We already use AI to translate reams of text, often with passable results. We’ve grown used to consuming imperfect language when the stakes are low: a twitter post, a menu, a news article. But the suggestion that translation as a craft can be replaced with AI is a category error, for the same reasons as above. Translation is not an act of mechanically swapping words between languages. It’s an act of cultural mediation, especially with fiction. A translator has to know not just what the author wrote but what the author meant, and how that meaning will be received by an audience with a very different set of assumptions, idioms, and taboos.

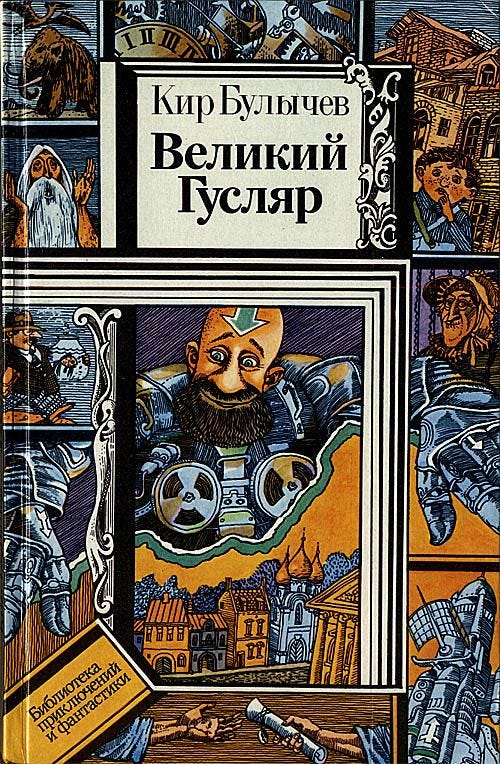

As it happens, I recently translated a short story by Kir Bulychev — a Soviet science-fiction icon virtually unknown in the West. (The translation is here, if you’re interested.) It took about five hours to produce six thousand words, the majority of which was spent editing a draft produced by ChatGPT.

(Above: the Soviet cover of a collection by Bulychev, from which the story was taken.)

From this I can tell you two things. One, there is no way LLMs in their current state are capable of replacing human translators for a case like this. And two, they do make the job of translation a lot less tedious. I wouldn't call it pleasant exactly, but it was much easier than my previous translation experiences. The initial draft was terrible in conveying tone, irony, or any kind of cultural allusion. Still, without AI a story like this would have taken me several weeks to translate and polish, instead of one afternoon.

In other words, AI will not enable the creation of quality translations for people who previously lacked that ability. That part still requires a human feel for the linguistic and cultural elements of the translation. But for those who are just looking to get a rough but passable translation (say, for research) it should work most of the time. And for those who would love to create quality translations but face huge opportunity costs and zero financial incentives, AI could lead to new possibilities.

The deeper risk is not that AI will replace historians or translators, but that it will convince us we never needed them in the first place. A tool that outputs polished, confident language with no sense of ambiguity or context is appealing to people who think facts will save us. But there is a vast difference between facts and truths. If we come to treat them as interchangeable, we cede interpretation to the machines and narrative power to those who design them.

So maybe Microsoft was right after all, just not in the way they think. Historians and translators may be the first to go not because their work is easy to automate, but because the interpretive element of their labor has always been invisible or, when made visible, dismissed as odious human bias. AI will replace them only in the minds of people who never understood what they were doing in the first place. Which, given how things are going, may be enough.

i like your translation but hate dropbox so i put it on sth better and also created an epub for those who want to read it without forced page layout https://gitgud.io/nanderer/myDropbox/-/tree/master/regardingHegemon

I don't think the paper means what you think it means? The actual paper is "Working with AI:

Measuring the Occupational Implications of Generative AI" on arxiv. Microsoft is trying to align tasks and occupations that are likely to use AI, not identify occupations that will be replaced by AI. The top 40 jobs unaffected jobs include dishwashers and embalmers.

They explicitly caution:

> It is tempting to conclude that occupations that have high overlap with activities AI performs will be automated and thus experience job or wage loss, and that occupations with activities AI assists with will be augmented and raise wages. This would be a mistake ...