Complaints about decadence leave me cold. All ages are decadent, it’s just the decadence is unevenly distributed. Typically it’s confined to a few palaces and churches and it sits there undisturbed, and people with access to these outposts are not troubled by their closeness to it. The problem starts when it spreads to the wider public — it’s the democratization of decadence that turns out to be the real issue.

I remember, in the opening weeks of the pandemic, a strain of thought on Twitter along the lines of “Well, at least we don’t have to talk about stupid bullshit like the Kardashians anymore.” Friends, being able to talk about stupid bullshit is the highest luxury good of an advanced civilization. It means you are sitting on the peak of your own little Maslow’s pyramid, other necessities taken care of and forgotten. It’s true that people in sieges are unconcerned with celebrities. Do not envy them.

I was thinking about this because I recently stumbled on a discussion of decadence that I found pretty unsatisfying. Ross Douthat, NYT columnist and author of a recent book on decadence, is reacting to a piece by Tanner Greer on the decline of great thinkers in modern life. Greer notes that in his Decline of the West (1926) Spengler could easily identify the great thinkers of his era, people like Tolstoy and Nietzsche and Marx, all near-contemporaries.

Where are our equivalents of these giants? asks Douthat. Looking over the past twenty years, he is pessimistic:

I can’t imagine anyone making a confident claim about contemporary philosophers and religious thinkers and would-be scientists of human nature that ranks them with Nietzsche or Marx or even Freud, with William James or W.E.B. DuBois, with Kierkegaard and Newman.

I have to say, that is a bit of a cowardly definition. Usually when people are worried about decadence they are concerned with shifting cultural norms around once-forbidden behaviors that have gained social acceptance. The decline of traditional gender roles, hierarchies, and national identities is the mainstay of decadence discourse. This is the reactionary face of decadence, tied to notions of decay of the national body and the parasitic creatures (Jews, foreigners, minorities) that feed on it.

As the conservative of the sophisticated centrist, Douthat cannot stoop to these tropes. He defines decadence in a more palatable way — as the lack of innovation. But even that circumscribed definition turns out to be incredibly narrow. It’s not true for science or technology or, as he admits, for literature. His main complaint turns out to be that we’ve had no great social thinkers over the past 20 years. Our sin is relitigating the cultural debates of the Baby Boomers instead of coming up with our own.

Note that by Douthat’s definition of decadence Spengler has nothing to worry about, so it’s a bit ironic to evoke him here. There is also some chronological sleight of hand happening. Spengler is writing in 1926 about people who died 15-45 years ago and produced their most famous works in the half century or more before. The Manifesto is 75 years old by that point!

But let’s grant the premise that we’ve had no great thinkers in the recent past. The kinds of world-historical thinkers Douthat yearns for transcend disciplinary boundaries and have important, big things to say about society as a whole. They take on huge subjects — Marx and capitalism, Freud and the mind — and try to extract from them concepts that find utility across social sciences. In many ways, they are holists, weaving together elements of the human experience by using powerfully simple concepts.

I think what is really meant by “great” here are thinkers that are universally agreed upon to be important. And universal agreement becomes increasingly difficult when the canon is fragmenting. Now, it could be that we’ve failed to produce great social theorists because we’re out of big ideas. But here is another reason: the increased complexity of social life makes big claims increasingly untenable, and attempts to do so will sound like glib caricature instead of penetrating insight. (Hence the rise of thought leaders.)

Social science has evolved by fragmentation. Something is lost when that happens, but I’m not sure it’s unhealthy. Each field has their own stars but they shine on increasingly smaller worlds. Is this decadence, or division of labor? We don’t think of science as stagnant because the era of “the great scientist” is over, or because laboratories and not lone geniuses now shape scientific innovation. The specialization of the scientist is proof that science has advanced.

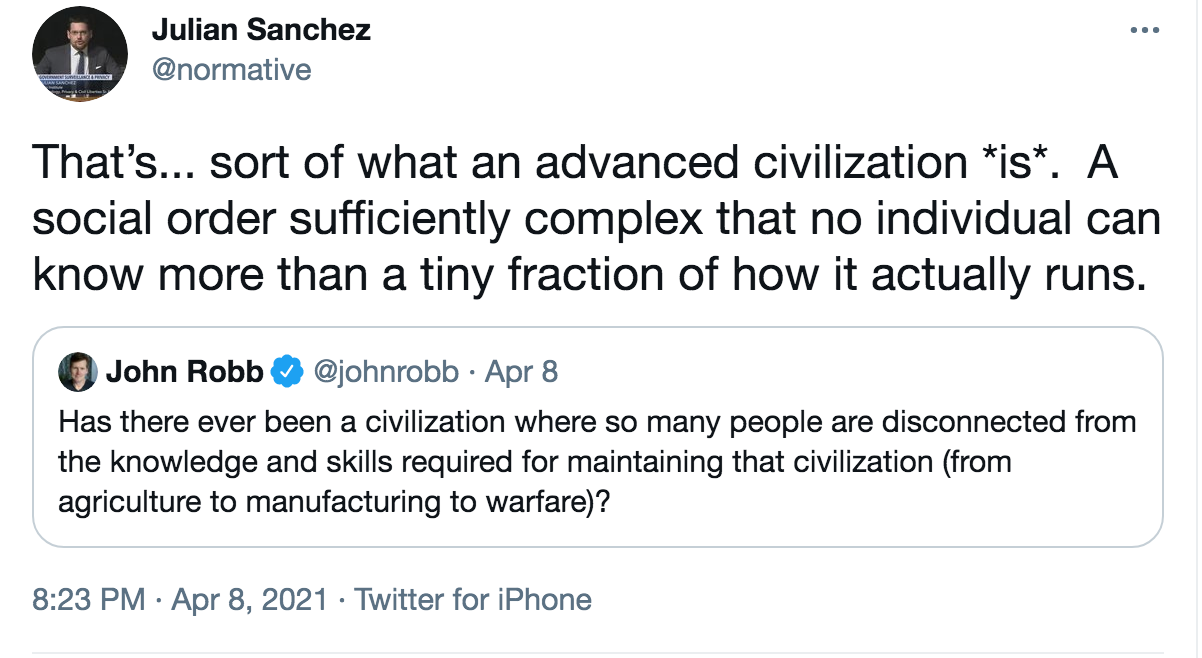

Someone on Twitter recently complained about our disconnect from the foundations of our own civilization. It’s the sort of plausible cliche that will uncontroversially collect likes and retweets. But I thought one particular response was useful:

If you think a universally agreed-upon canon is the mark of stable civilization, then its fragmentation will seem like decadence. And losing the thread of an intellectual narrative running through history will feel like a form of breakdown.

John Ganz, in his response to Douthat, writes:

Suffice it to say, I’m a little suspicious of the narrative of decadence, not the least of all for its implicitly or explicitly reactionary politics, but I admit I’m also attracted to the idea. I’ve always loved cyclical theories of history that propose periods of civilizational senescence and renascence, even though I think it’s not quite real on some level. It’s quite Romantic. Or it’s a continuation of Romanticism by other means: it takes all the mundane, boring, exhausted experiences of everyday life and puts them on stage with the drama of civilizational decline and downfall; everyday life becomes a little bit more Wagnerian. In other words, it quickly does a lot of literary and imaginative work.

It’s an excellent essay and you should read (it’s how I stumbled on the discussion in the first place). But on a purely personal level I find the Romantic reading of decadence a bit generous. More often the feelings it produces, in those who actually practice the politics of anti-decadence, range from contempt to violent nihilism.

Still, appeals to decadence will always resonate because they tap into our disgust with modern society. That’s a reason to be skeptical of them — it’s always easier to be disgusted at the society you have no choice but to inhabit. But it doesn’t mean the appeal is illegitimate. I don’t know, maybe my antipathy to the concept just blinds me to its presence. It did make me think about how little IR scholars examine the concept of decadence, despite our occasional embrace of cyclical arguments like hegemonic transition theory. Perhaps it’s because we tend to see decline as a sort of historical reversion to the mean, driven by material rather than cultural forces. Or perhaps it’s because most of the “history-is-cyclical” people gravitate to the realist camp, where interrogating the notion of vapid luxury is itself going to be seen as a vapid luxury. Nevertheless, the concept is implicit in books like Jack Snyder’s Myths of Empire or Mancur Olson’s Rise and Decline of Nations.

I probably need to take the idea more seriously. But decadence as lack of intellectual consensus doesn’t stir me. Yes, history is filled with the sound of silken slippers going downstairs and wooden shoes coming up. A fragmented canon does not qualify as a silken slipper.

NEXT TIME: Back to IR — Russia, China, and the geopolitics of regime promotion in Asia.

Very interesting. Douthat clearly off the mark, and I think Ganz nails it. If we're talking about 'decadence' as part of the historical cycle, some of it is clearly survivorship bias (the only polities that we care about when they collapse are once that hit some level of material comfort and cultural distinction), and some is simply a more moralistic framing for institutional capture. Society generates wealth, and power accumulates in the hands of the wealthy, in ways that may run counter to the aims of the state. And as rents grow, the incentives to fight over control of those rents grows too.

But he does maintain that science has stagnated. Read his book; I think his piece sort of assumes you have already read that first.